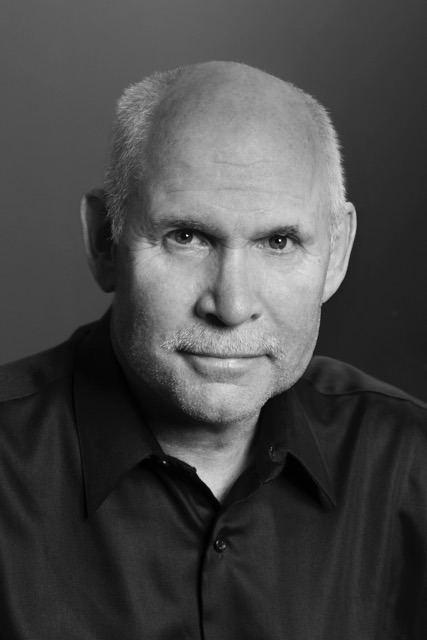

Lucie Foundation has recently opened House of Lucie, a new art space in Bangkok, Thailand. During the opening reception on November 14, 2016, Hossein Farmani, the founder of Lucie Foundation, introduced “A Lifetime of Work” exhibition by Steve McCurry.

Best known for the “Afghan Girl” portrait of a refugee featured on the cover of National Geographic Magazine, Steve McCurry appeared at the opening event and met with local photographers and fans.

Many visitors were drawn to see the images that McCurry took over the decades. Some of them were on display for the first time.

House of Lucie had a chance to meet the photographer and ask him a couple of questions.

ABOUT STEVE MCCURRY

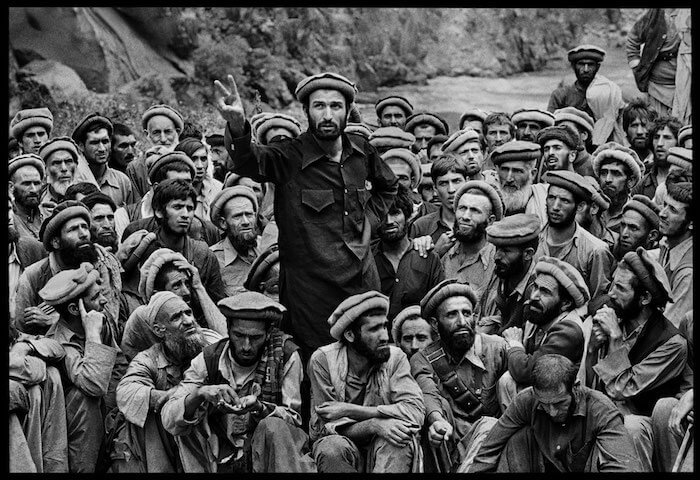

Steve started his career working for a newspaper. He then traveled to India where he crossed the Pakistan border into rebel-controlled Afghanistan just before the Russian invasion. He was the first to capture the haunting realism of the conflict.

McCurry has covered numerous international and civil conflicts. He has photographed the Iran-Iraq War, Beirut, Cambodia, the Philippines, the Gulf War and the continuing strife in Afghanistan. He often risks his life to capture his images from the front lines, and he has survived many close calls. He was arrested and chained in Pakistan, beaten and almost drowned by zealous crowds at a religious festival in India, and nearly killed by the Mujahadeen. He survived a plane crash in Yugoslavia, and he twice has been reported killed.

Steve’s career high point was undoubtedly the National Geographic cover photo of the previously unidentified Afghan refugee girl, whom he located and photographed again nearly two decades after the original. That picture has been described as the most recognizable photograph in the world today.

How did you get to where you are now?

I love what I do. Having that passion is necessary to succeed, whether your field is photography, writing, painting, filmmaking, dancing, or medicine. Once you find something you love, then you have to work hard, develop discipline, and refine your craft. That’s what has gotten me to where I am now.

Who, or what, deserves a lot of credit for where you are today?

My father set a great example for me early on, regarding hard work and discipline. I’ve worked with my sister, Bonnie, for over 25 years—we collaborate on all facets of my work. She deserves a lot of credit for my success. Finally, I owe a lot to my university professors, who helped set me on the right course for having a discerning eye in photography.

How do you choose the places you go to photograph?

I chose places that I’m interested in. For me, photography and travel go hand in hand. I’ve always been very curious and driven by a need to explore and wander, and photography for me is the perfect companion to that need. Photography has been the perfect way for me to see the world and to experience different cultures. This has remained the main drive in my work, and in my life.

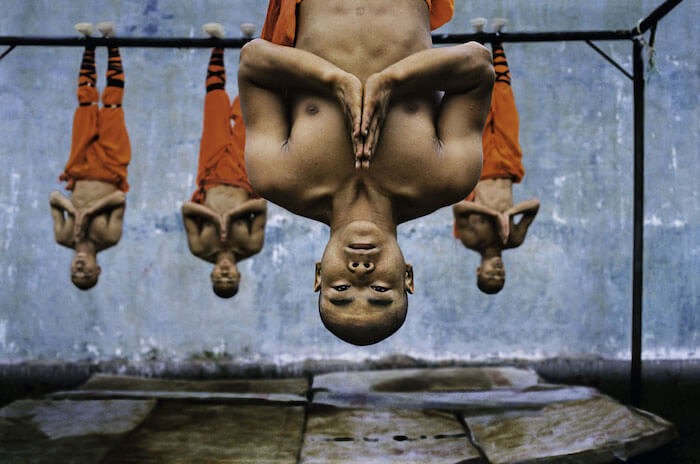

Shaolin Monks Training, Zhengzhou, china, 2004

And how do you prepare for your trips?

I research a location before I arrive, so I have good idea of what I’m going to do. On the other hand, it’s also best to go to a place without many pre-conceived ideas, because things change: guidebooks become outdated, and things close or disappear. I usually get to a place and immerse myself in the situation and then go from there.

Too much preparation can lead to procrastination. The main thing is to get out and shoot and minimize the amount of time spent researching.

Camels and Oil Fields, Al Ahmadi, Kuwait, 1991

Have you visited the places you photographed in the 70s and 80s recently? How did these places change with time? Which country is your favorite for taking photos?

I’ve returned to Afghanistan several times, and I would say that Afghanistan is becoming an increasingly difficult place to photograph. It’s dangerous to be on the streets, especially with a camera; anybody with a camera is liable to be targeted, kidnapped. And many people are generally not open to being photographed.

India was the first place I traveled to as a young photographer, and I’ve also returned there many times, drawn to its rich mix of cultures and customs. Since my first visit in 1978, I have seen India’s economic and social transformation. You cannot find another country with such a rich and varied geography and culture amid the chaos and confusion. As with other places, the rise of technology and access to the internet has greatly changed India.

Nonetheless, some things don’t change in the country. About 25 years ago, I photographed a shoe cobbler in Jaipur. Earlier this year, I returned to the area and happened to walk down that same street. The same man was sitting in the exact same spot. He now had gray hair, and was 25 years older, but looked pretty much the same. It was amazing how little had changed: same scene, same situation, 25 years later.

Woman in Canary Burqa (Kabul, Afghanistan, 2002);

Village Boy (Kamdesh, Nuristan, Afghanistan, 1992);

Girl Prays (Afghanistan, 2003)

Portraits are at the center of your work, how do you interact with your subjects? And break language and cultural barriers?

When first interacting with potential subjects to photograph, I always try to establish a friendly smile and treat them with respect. Most people agree to be photographed. For me, the key to communicating with someone with whom I don’t share a language is in having an understanding of the situation and nuances of your relationship with that person. It always helps to have someone with you who knows the local culture and can best tell you where you should and should not go as an outsider.

I think we’re all fascinated with each other; we all have the same face but yet we’re all different. That difference is fascinating because so often there’s an incredible story told on our faces. So much of portrait photography is waiting for the right moment when a person’s personality reveals itself.

Mujahideen, Afghanistan, 1980

Do you think the world is becoming more and more homogenous? How do you still manage to find unique places and stories to tell through photography?

Yes, the world is becoming more homogenous. Not completely, but it’s very different from the way things were years ago, when places like Russia and China had state-controlled media with numerous restrictions and barriers. While there are still restrictions, these days when I travel, I see almost everyone—including street sweepers, fruit vendors, the poorest people—having a cell phone. Being able to see the world through your phone and the internet, and being able to call anyone in the world, has definitely changed the way of life everywhere. Also, you now see the same clothing everywhere: such as a sports tracksuit made in China in millions of units, which gets distributed to every country in the world.

As for finding unique places and stories, I don’t believe my work is only about undiscovered tribes and remote places. I think people can find unique stories in their own back yard, which for me is New York City, where I live: I’ve shot many photos in the city. Being a good photographer doesn’t necessarily mean you travel to distant places.

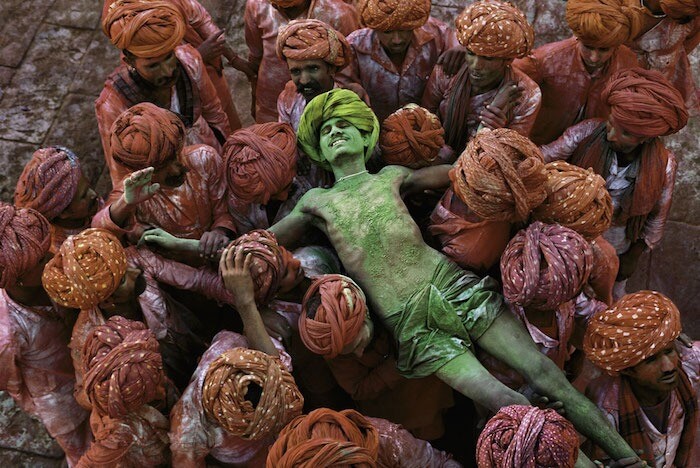

Holi Man (Rajastan, India, 1996); Young Monks Play Video Games (Bylakuppe, India, 2001); Mother and Child at Car Window (Bombay, India, 1993)

If you had to choose a different field other than photography, what would it be?

If I was not a photographer, I would probably be a filmmaker. During college, I studied film and I have always been compelled to share people’s stories. It has always been about the story for me, and film is another medium to convey a story about a particular time and place.